“In Memory of George Floyd 1974-2020”, Keyvan Shovir, 2020

The following article was posted in The Right Stuff on January 8, 2021:

Art Activism and Human Rights: A Bay Area Perspective by Sarah Jury

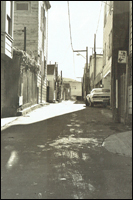

This past November, on a trip to the Mission District in San Francisco, my friends and I stumbled across an alley tucked slightly away from the street that was full of beautiful street art. I instantly became enthralled by the bright colors and imagery of these murals spanning the entirety of this corridor, but, after taking a closer look, phrases like “Stop Killing Our Children” and “Abolish ICE” jumped out at me. These paintings weren’t created for Instagram photoshoots, rather they highlight systemic civil and human rights abuses such as police brutality, anti-immigration policies, even apartheid. This public display, which I later found out is known as the Clarion Alley Mural Project (CAMP), is a beautiful representation of people looking to inform and inspire through their art and is demonstrative of a larger culture of art activism unique to the Bay Area.

The connection between human rights and art may not seem obvious, but it does run deep. Similar to the role of news media, artists can bring attention to human rights violations and horrific tragedies through shocking depictions that force audiences to acknowledge them. This social justice art has underlying messages that push for greater structural reform within society. And, unlike the news, it relies on using images to elicit emotional responses in viewers. A key historical example of this is Pablo Picasso’s Guernica which depicts the bombing of civilians in a Basque town by the Germans during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Although abstract, this work clearly depicts the terrors of the situation and helped fuel public outrage towards both this war and war in general.

Visual art may play a key role in creating public reaction towards current issues but this is harder to do when it’s locked up in a museum. Although essential for preserving historically significant works, this method of displaying art limits the audience able to view and therefore react to it. With the goal of promoting human rights in mind, public art, whether that be through commissioned murals or graffiti on a freeway overpass, is much more successful. Since anyone and everyone has access to it, it can more easily raise awareness to pressing community or societal concerns. One of the pioneers of the muralist movement, Diego Rivera, did this through his murals focusing on the protection and empowerment of workers done both in Mexico and the US in cities like San Francisco where many of his paintings still remain to this day. Having his work on public display meant that his message of social justice reached more people, including Franklin Delano Roosevelt who was inspired by Rivera in creating social welfare programs within his New Deal that helped pull the US out of the Great Depression.

Rivera is one of many examples in a long history of raising awareness for a diverse range of human rights through art in the Bay Area. Emory Douglas, the minister of culture for the Oakland-based Black Panther Party, used his illustrations within the Party’s newspaper to empower black citizens to challenge abuses made against them by the police and US government. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, many of his symbols still have meaning to this day, including pigs as a symbol of oppression by government and police. Another important piece of activist art in Bay Area history, The Pink Triangle, has been installed on top of Twin Peaks in San Francisco each year since 1996 for Pride Weekend. This image, once synonymous with the label for homosexuals in Nazi concentration camps, is now a symbol of pride for those who identify as LGBTQ+ and highlights how this community still faces persecution throughout the world. Art is entwined in the Bay Area’s reputation as a center for social justice and change, and walking through the streets of San Francisco, it is easy to see the continued impact it’s had on this community.

When I discovered CAMP in the Mission District, I caught a glimpse at how this creative tradition is being translated to reflect the current concerns plaguing our community and country. This project was first created in 1992 as a challenge to gentrification in the neighborhood and has hosted over 500 artists creating over 700 murals throughout its history. According to CAMP’s website, it has a mission of “support[ing] and produc[ing] socially engaged and aesthetically innovative public art as a grassroots community-based, artist-run organization in San Francisco”. Its murals, which are constantly changing, highlight abuses similarly to Rivera’s murals and Picasso’s Guernica. They are therefore an important tool in promoting and educating about human rights. But, unlike Picasso and Rivera, CAMP’s paintings are not stagnant but rather evolve with public discourse. In one mural highlighting police brutality, the words of a past work just barely peek out behind portraits of George Floyd and Breanna Taylor and a bright yellow background. In this way, displays like CAMP work in tandem with news media and human rights organizations to alert the public to current concerns. As put by J Manuel Carmona, an artist based in San Francisco, “public art is not a choice, you have to see it”. Having the potential for reaching such a wide audience means that displays like CAMP are highly effective in informing and advocating.

Oftentimes the message of these paintings involves taking an international issue and making it more personal in hopes of creating an emotional response. For example, a mural promoting LGBTQ+ rights depicts a diverse group of people marching down a street in San Francisco. By including a familiar setting and figures that the audience may relate to, this painting establishes a personal connection to viewers that can better resonate with them. This is especially important because the theories of international human rights can be hard to conceptualize without the ability to see them in action. By relating these transnational concepts to the community, this public art display reveals how the ignoring of these essential norms by those in power affects daily life for so many. In general, public art gives marginalized peoples a medium to voice their grievances against society and to inspire their audience to respond in ways big and small: from raising awareness by sharing their work on social media to passing legislation, similarly to President Roosevelt after seeing Diego Rivera’s murals.

Art in the use of human rights has a long history in the Bay Area and continues to play a major role in promoting activism within this community. Although CAMP is a wonderful example of this, there are many other similar projects, such as a new mural being created in Oakland’s Liberation Park by artists Rachel Wolfe-Goldsmith and Joshua Mays to celebrate social justice and diversity. This continued dedication to change is what sets street art (and especially Bay Area street art) apart from other types, as it ensures the public remains aware and defiant of abuses targeting marginalized groups. By raising awareness for human rights, art activism empowers audiences to take action against corruption and neglect in hopes of creating a more just and equitable community and society.

- “Enough is Enough Stop Killing Our Children”, Mel Waters, 2018

- “End Apartheid B.D.S”, Megan Wilson, 2018

- “We All Deserve a Healthy and Safe Community”, Hospitality House, 2016

- “Justice”, Cliff Hengst, 2018

For more info on CAMP and the artists showcased in this article check out:

https://clarionalleymuralproject.org

https://www.hospitalityhouse.org/community-arts-program.html